Back to the Basics: Can’t Buy This Way of Life

A Moment’s Pause with Thailand’s Hilltribe People

During an era of increasing political tension and societal unrest, this is a story about our shared human condition and the social-ecological impacts of capitalism ‘development’ and ‘modernity.’ This is about taking ‘a moment’s pause’ in order to ponder the vital importance of our varying cultures and the intrinsic value of our heritages. We consider this global phenomenon in the context of northern Thailand’s hilltribe people (‘highlanders’) and an ethnic Karen community striving to maintain its cultural traditions and vital indigenous knowledge. What does this mean for Us all?

Sitting on the well-worn floor of an airy bamboo-constructed Buddhist temple-house, Tior, 49, pointed to a separate room behind him which shelters the village’s sacred well. While the mouth of this spring had barely enough water to scoop into a ladle, he told us that it symbolically serves as the cultural heart-center of Baan Nam Bor Noi (in the Thai language means, ‘village with the little well’).

Sitting on the well-worn floor of an airy bamboo-constructed Buddhist temple-house, Tior, 49, pointed to a separate room behind him which shelters the village’s sacred well. While the mouth of this spring had barely enough water to scoop into a ladle, he told us that it symbolically serves as the cultural heart-center of Baan Nam Bor Noi (in the Thai language means, ‘village with the little well’).

“This is sacred land,” said Tior, who has resided in Nam Bor Noi since it was established decades ago. “This land belongs to Kru Ba Wong, the great monk whom we villagers worship from our core. He taught us to follow Buddhist principles, be good people, eat vegetarian, not modernize, and maintain our culture. I want to preserve this.”

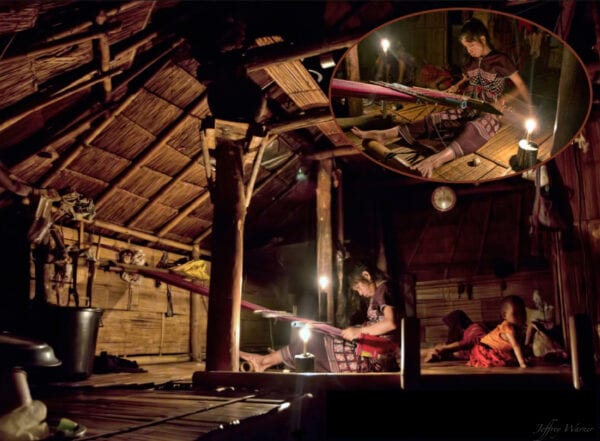

Nam Bor Noi, a fifty-three household 200-person ethnic Pakagayor (a.k.a. Karen) village community located in northern Thailand’s Lamphun Province, is a one-of-a-kind place. It is a community of devout Buddhists and strict vegetarians who exist essentially apart from the modern world. Those who live here use no electricity. Villagers utilize a hand-crank-operated bucket to draw water from holes they had manually tunneled through the volcanic lava bedrock beneath their feet.

This community outwardly appears to function smoothly and naturally. There is a distinctive odor that permeates the village; perhaps it’s the lava rock mixed with the sweet scent of wood-fire smoke. The village is almost eerily peaceful. Many of the adults sit around while doing embroidery and crafts, while children play games; they use the simple wonders of their natural environment as the playground. Gentle laughter while the young and the old interact with one another is pleasing to the ear, heart, and soul.

The feeling one might get while in this village is that of being in the present moment. It at least appears evident that everyone here is actually living, here — not wishing so much that they were somewhere else. Perhaps a reason for this is that the machine world is totally absent in Nam Bor Noi. What is moving here is largely only the machinery of the human body.

The feeling one might get while in this village is that of being in the present moment. It at least appears evident that everyone here is actually living, here — not wishing so much that they were somewhere else. Perhaps a reason for this is that the machine world is totally absent in Nam Bor Noi. What is moving here is largely only the machinery of the human body.

Like many human communities, even those with peaceful and natural environments, there are social problems in this village. However, there is far less apparent stress than life in the city, which involves fighting with the madness of traffic jams or an office clock. None of this exists in Nam Bor Noi. Or, perhaps it’s just in different forms from that of the urban realm.

Still, there is a noticeable difference between this village and the modern city hub, such as the lack of noise racket! There are no airplanes soaring overhead; there is no clattering construction equipment or industrial factories; there is nobody in cars or on motorcycles competing for the roadways; there are no sounds of television or attention-sucking internet distractions, and there are no bars with karaoke machines or other riff-raff.

There is the occasional cackling of a battery-powered radio. There is the sound of wood being chopped. There are the hammering and grinding sounds from handicrafts being forged. There are the footsteps of villagers, as they lug buckets of sloshing water across their shoulders.

Muffled conversations coming from thatched bamboo homes capped with teakwood leaf roofs can also be heard. Peeping birds flutter overhead; at day’s end, the birds’ songs are replaced with the chirping of jungle bugs.

“This village is very special,” said Tior. “It’s not just foreigners who want to observe our way of life. Other Karen villages need to see this as well. We want to teach others how to live like this. We want to preserve our ways of life. This way of life is healthy. It’s something that money cannot buy.”

The Non-Romantic Reality for Thailand’s Hilltribe People…

As utopian as this all may sound, life can be damn hard for villagers, as there are few avenues by which to earn a living. Many, versus living sustainably with and from their surrounding environment, as their ethnic group had done for generations, now must work paying jobs, none of which are highly desirable. This includes in urban areas, or by doing hard labor for private landowners and corporate agro-companies, for a pittance.

From January until March, they hand-harvest corn and maize, collect leaves and grass for roofing materials, as well as dig lava rock that is largely used for construction purposes. April through June is Thailand’s dry season, so there is little to no agriculture; villagers clear land or do any kind of work that they can find.

From January until March, they hand-harvest corn and maize, collect leaves and grass for roofing materials, as well as dig lava rock that is largely used for construction purposes. April through June is Thailand’s dry season, so there is little to no agriculture; villagers clear land or do any kind of work that they can find.

The off-season is also time to create handicrafts such as necklaces and utensils made from coconut shells and other materials. They will sometimes work on a dress, a shirt, or other types of craftwork for a week or more and then sell this product for whatever small amount of money “the market rate” allows.

From July to November, villagers harvest longan fruit, prune trees, tend gardens, dig lava rock, or plant rice. December is rice harvesting time. All hands on deck, on land that does not belong to them!

Nowadays, there are expenses such as the purchase of rice and other food staples, lamp oil, clothing, toiletries, school uniforms, and shoes. For a five-person family, total monthly expenditures average about US$80. Some households can save between US$30-$150 per year, which they generally reserve for medical expenses. They live simply, to say the least.

While they do exist in a form of socio-economic poverty, their wealth is that Nam Bor Noi, alike most of Thailand’s hilltribe people communities, is one of the few places remaining that if the electricity grid or the material supply chain feeding the modern industrialized world were to collapse, its community members, at least those equipped with their culture’s traditional indigenous knowledge, could survive.

What is noticeably absent in this village are older youths; most of whom have left for larger towns and cities. Garbage has also become a new problem and can be seen along the village pathways and nearby roadways that used to be pristine and clean. Some Nam Bor Noi villagers exhibit signs of malnutrition.

An ethnic Palong woman and her grandson in Pang Daeng Nai village near Chiang Dao, Thailand share precious time together. The Palong is one of many of Thailand’s hilltribe people groups.

“We are not suffering,” said Tior. “Living like this is fine. It is a quiet and peaceful life…Other people feel like they need material things to be satisfied in life. I think the most important thing for a happy life is to have my own space and food; I can survive. Having a car is a small thing compared to this.

“Eighty percent of the villagers living here in Nam Bor Noi don’t need (or want) electricity or running water,” added Tior. “If someone in this community has money and needs these, or if they don’t follow the rules (that prohibit modernization), they can buy land elsewhere, build a house, and do whatever they want.”

Tior said that when all of us humans were born, we didn’t have anything; life was fine. But if we are greedy and selfish, it ruins our life and our relationships. “Our culture is becoming like this,” added Tior. “Actually, the natural world around us is just fine; people ruin themselves. … Everyone should be a good person. I don’t know if I’m a good person. I’d like to know how to be one. I do know that I’m not greedy or selfish.”

He said the Thai government offered utilities and even solar cell technology to this community, but the villagers rejected electricity as a fire hazard.

“We asked the government about who would pay for the electricity, water, and infrastructure repairs,” said Tior. “For me, I would like to have more light when I’m eating. But I am okay. A major challenge I face nowadays is finding roofing materials for my house. The climate has changed, and the grass is now hard to find. The leaves used as an alternative last only a couple of years.

“I worry most about land ownership,” added Tior. “I don’t have any rights to this land; the government owns it. … If I don’t have land for growing rice, for eating, this is a big problem. Sometimes, there is no work. I worry about this too, and getting sick, but not too much…

“I want to transfer to my children what it feels like to live in the traditional way,” he added. “We (in Nam Bor Noi) support preserving this way of life…We want to keep it special.”

The Sacred Land and Vital Rituals of Thailand’s Hilltribe People…

Every evening, many Nam Bor Noi residents, including most of the children, congregate at the sacred well while dressed in their traditional clothing. They place offerings from nature and incense sticks to their revered late monk who founded this settlement area forty-five years ago. The congregation then turns around to face the temple located one kilometer away, where Kru Ba Wong’s embalmed body is displayed, before meditating en masse for fifteen minutes.

“There are many things with development that are surrounding us now,” said Tior. “This nightly tradition is very important for our cultural protection.”

The Seismic Societal Shift of ‘Development’…

‘Development,’ with its tenet of ‘giving people more choices,’ is predominantly heralded as a positive thing. It is commonly linked with notions of ‘progress,’ particularly in the forms of modern necessities such as healthcare, financial security, mainstream education, and other aspects perceived as good for human well-being. This is coupled with technological innovations that make life easier and more physically comfortable, also facilitating access to the globalized world (i.e., the internet). Sounds good, yes?

‘Development,’ with its tenet of ‘giving people more choices,’ is predominantly heralded as a positive thing. It is commonly linked with notions of ‘progress,’ particularly in the forms of modern necessities such as healthcare, financial security, mainstream education, and other aspects perceived as good for human well-being. This is coupled with technological innovations that make life easier and more physically comfortable, also facilitating access to the globalized world (i.e., the internet). Sounds good, yes?

Dr. Jan Nederveen Pieterse, a prominent scholar of global political economy, development studies, and cultural studies, offers in his book, Development Theory: Deconstructions/Reconstructions, another perspective on development’s root motivations. Pieterse defines ‘development’ as “an organized intervention in collective affairs based on a standard of improvement.”

In other words, ‘development’ is about enacting top-down government policies that interrupt, even decimate, a society’s culture. This is in order to install institutions (i.e., enmeshed with western democratic capitalism) that facilitate access to and participation in the global market system.

Pieterse writes, “In the age of globalization, local culture represents the treasure trove of the Golden Fleece – perhaps the world’s last. The world’s indigenous peoples are the last custodians of paradises lost to late capitalism, ecological devastation, McDonaldization, Disneyfication, and Barbiefication. With ecological pressures mounting worldwide, this ethos is gaining ground as if queuing up for the last exit.”

‘Ethos,’ according to the Oxford Dictionary of English, is the ‘characteristic spirit of a culture, or era, or community as manifested in its attitudes and aspirations.’ Cambridge Dictionary refers to ‘ethos’ as ‘the set of beliefs, ideas, etc. about the social behavior and relationships of a person or group.’

It could be perceived that Pieterse’s reference to ethos and “custodians of paradises lost” is inferring that rural indigenous communities are, or once were, paradises free from environmental and socio-ecological ills. It required years of my own fieldwork to realize (and accept) that while many of northern Thailand’s indigenous communities, for example, may dwell in ‘nature’ abundant areas that appear social-ecologically idyllic, this utopia is simply not common reality.

Elements of this are inherent to and still palpable in at least the indigenous communities I’ve visited. But this is, and northern Thailand’s hilltribe people are, under threat. For capitalism ‘development,’ as ‘an organized intervention in collective affairs based on a standard of improvement,’ erodes these vital facets of human society. Whether systematically or by semi-unintended default, ‘development’ retrofits people and our communities into some means-to-an-end combination of capitalism’s tenets of land, labor, capital, and market. It is actually anti-human.

This said, what about the ‘de’ of the word ‘development?’ What is development taking away from our cultures and our traditional ways of life? What are the societal replacements? What are the short and potential long-term impacts? What does this mean for all us humans? Really; what is the end-game of this unsustainable ‘natural resources’ extractive global market system?

A Regional Dilemma for Lowlands and Highlands Dwelling Folks…

For further context into this topic, let’s consider the region amid which Thailand’s hilltribe people reside and how they are part of this saga.

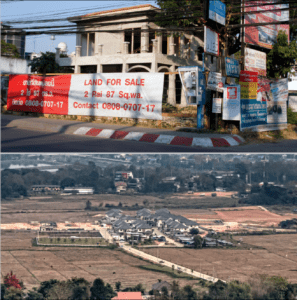

The rapid development of Chiang Mai city, located about four hours from Nam Bor Noi, and is considered Thailand’s second capital, over the past few decades has dramatically altered its traditionally slow-paced and conservative culture into a mini-Bangkok metropolis. This is particularly evident with worsening traffic congestion, pollution, and increasing social tensions. Farmers are selling their generations-old properties. Rice paddies are being filled with concrete, making space for condominium complexes and shopping malls. These phenomena are drastically altering the geographical and social-ecological composition of the Thai north. This is having a profound effect on how families and individuals interact with each other and with their natural environment.

Farmers are selling their generations-old properties. Rice paddies are being filled with concrete, making space for condominium complexes and shopping malls. These phenomena are drastically altering the geographical and social-ecological composition of the Thai north. This is having a profound effect on how families and individuals interact with each other and with their natural environment.

What can also be observed is shifting demographics including regional migration issues, societal homogenization involving the national acculturation of indigenous ethnic peoples, expanding income inequality and additional societal stratification, competition for space, and other unplanned changes.

Some rural populations here still function in a similar fashion to before the prominent onset of urbanization. However, this is rapidly changing. The global market system, and various lifestyles associated with the modern world, is perforating their social fabric. Homogenizing ‘modern world’ culture is replacing ethnically traditional lifestyles. This is affecting everyone, including those living in remote rural areas.

Northern Thailand’s ‘Hilltribe People’ (‘Highlanders’)…

Thailand’ hilltribe people are comprised of ten officially recognized groups. They are the Karen, Hmong, Akha, Lisu, Lahu, H’tin, Khmu, Lua, Mien, and Mlabri, totaling over 926,000 people, according to the Asia Pacific Human Rights Information Centre and Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand. These ethnic groups are some of Thailand’s most marginalized of the marginalized.

Kitthiphum, who is ethnic Black Lahu, was proud to have Thai citizenship, although this isn’t the case for many highlanders.

Commonly referred to as “hill tribes, and “hilltribe people,” another name that has been used is chao khao (meaning, “hill/mountain people”). They have also carried the derogatory label of chao pa — chao meaning ‘people’ and pa meaning ‘forest.’ This has the connotation of them being ‘wild people,’ or the opposite of ‘civilized.’ A more recent, politically correct, term used for Thailand’s ethnic groups is “highlanders” or “highland Thais” or even “Thai people in the forest.”

According to the Asia Pacific Human Rights Information Center and Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand, “In opposition to these negative connotations of the official designation, chao khao, or other commonly used derogatory terms, indigenous organizations and indigenous peoples’ rights advocacy groups began to promote over ten years ago the term, chonphao phuenmueang, as the translation of “indigenous peoples.”

The Thai government has been campaigning to reject the term ‘indigenous peoples,’ as an element of its decades-old ‘Thai’ national cultural building campaign (e.g., the “12 Culture Mandates”). The government at least explicitly considers these groups as much ‘Thai’ as other Thai citizens. It is proclaimed that they can experience the fundamental rights of Thai citizens.

The reality is that northern Thailand’s hilltribe people continue to endure the same historical stereotyping and systematic discrimination as do other indigenous groups worldwide. Although many of these communities have for generations lived in northern Thailand’s mountains, many are still not considered Thai nationals. Therefore, some do not have Thai citizenship necessary for receiving government social benefits, among a multitude of other (sometimes life-threatening) issues.

These groups have also been forced, through public policies, to become part of a modernizing trend. This is increasing their inescapable dependence on local and world market systems traditionally alien to them for survival. For the most part, villagers can no longer live in their traditional manners. This overall situation is having a profound impact on their ways of life, making their future uncertain.

Territorialization of Land and Culture…

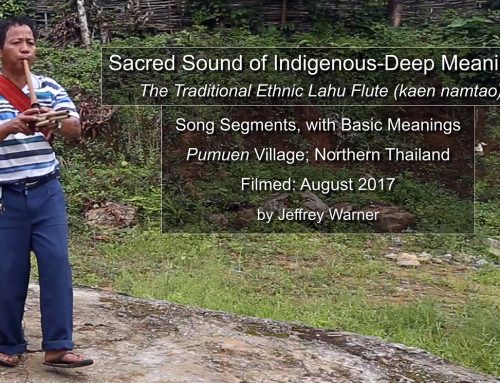

An explanation of this image is available here.

The Thai government implemented land-use regulations in the 1950s, by officially considering, therefore placing, ethnic communities inside national park and ‘reserved forest’ territory. This rural development scheme essentially corralled previously independent mountain-dwelling villagers into a top-down State control system that determines how they earn a living.

Traditional slash and burn shift cultivation practices, central to villagers’ sustainable livelihoods, were banned. Essentially, they were force-converted to farmers of sedentary orchard agriculture. Forest products, regarded by some village communities as common pool resources, are no longer legally theirs for harvesting.

This may appear to some as a minor inconvenience; however, if viewed through a social-ecological lens, the entirety of villagers’ lives (e.g., livelihood, textiles, language, music, oral traditions, etc.) traditionally revolves around the harvest cycle. If these socio-cultural systems become altered, as they were in northern Thailand, a situation ensues whereby people are rendered essentially in an identity crisis of sorts, until another system can be structured and implemented (if at all).

The policy scheme used for perpetuating this is the Thai Royal Project, pioneered by the revered late King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX). He for decades worked closely with Thailand’s hilltribe people.

This development project had, and still has, the explicit purpose of solving problems associated with highland deforestation, as well as poverty and opium production by promoting and growing alternative cash crops such as tea, fruit, flowers, and vegetables. What is predominantly not discussed is how this top-down rural development initiative has also resulted in detrimental social-cultural impacts for the Project’s subjects.

Farlae, of ethnic Black Lahu ethnicity, ventured deep into the forest with her friend and sons, in order to scour the river for fish and other aquatic creatures. It was vitally necessary. For a hail storm (a fairly new climate change-related phenomenon here) had temporarily destroyed her family’s tea trees; this means they had no cash crop-derived money for purchasing food. … Farlae, born and raised in the Thai highlands and with no electricity or other modern amenities, is adamant about passing forward indigenous knowledge to her children, in order to bolster their resilience during tough times.

In 1961, the Thai State Park Act was ratified. This policy instituted the further establishment of national parks and other forest conservation areas, all managed by the strict authority of the Thai Royal Forestry Department. This brought with it a plethora of further major changes for rural highland communities. This includes stringent land-use regulations Thailand’s hilltribe people, that greatly impacted their culturally traditional practices including hunting and fishing, as well as their collecting of wood, medicine, and forest food, among other ecosystem services related aspects.

Jabate, who is ethnic Black Lahu, and his village’s last living traditional medicine man, taught young villagers about the plants and herbs they’d harvested from the jungle on that day. He first shared his knowledge with the older youth, as they placed clippings into a folder and wrote the related information; then these youths taught the younger ones. This was a cultural insurance policy. As the pool of youth who would normally step forward to absorb his cultural knowledge are for the most part no longer interested. Villagers now have electronics and motorcycles. They go to the city and also depend on ‘modern medicine’ for the treatment of their illnesses. The last I heard is that the scrapbook the youth were using on this day, containing millennia of indigenous knowledge, had become lost.

For agrarian societies, particularly those with animist spiritual beliefs, all of these traditional practices are vitally linked with their overall survival mechanisms. If these societal systems are drastically altered or severed, a form of irreversible ethnocide ensues.

A Social-Ecological Transformation for Thailand’s Hilltribe People…

In the village, alcohol and methamphetamine addiction is an ever-growing socio-cultural by-product of this brave new world that co-exists with those villagers who are still attempting to live a quiet village life and are struggling to maintain the norms and values associated with their traditional culture.

In the village, alcohol and methamphetamine addiction is an ever-growing socio-cultural by-product of this brave new world that co-exists with those villagers who are still attempting to live a quiet village life and are struggling to maintain the norms and values associated with their traditional culture.

Overall, the villagers appear to be in shock, desperately trying to maintain their traditions while adapting to the encroachment of a modern lifestyle that is pulling them in, particularly the youth, one television program at a time. For many villagers, it’s as though they’re simultaneously living fundamentally different ways of life — a mixture between their cultural heritage and that of the mainstream modern world.

Many villagers, much like in what people may consider supposedly ‘civilized’ or ‘advanced’ cultures, now want to keep up with their modernizing neighbors but don’t really know how to cope with their rapidly changing environment.

The younger generations are looking to the outside world for examples of how to survive in modern society. They neither have little to no clue which world existence paradigm they should identify with nor to which one they belong.

For example, one can witness the stark contrast of a young Thai-speaking villager clad in his or her traditional ethnic clothing while also wearing caked-on makeup or a hairstyle mirroring modern Korean hip-hop culture. The middle-aged villagers want to preserve their culture for which they feel responsible; however, they often don’t know how, and are also being enticed by modernity related conveniences. Many of the elders can’t identify with any of this ‘modern world.’ What is ensuing for many of Thailand’s hilltribe people is a very real and tangible identity crisis.

The Looming Matrix for Thailand’s Hilltribe People…

I metaphorically compare this ‘development’ phenomenon to a scene in the movie, “The Matrix.” The machines (i.e., ‘development’ and ‘modernity’) had taken over Planet Earth. The remaining members of the human species, who were the resistance, had retreated to a domed and fortified room located at the Earth’s core. This could be symbolic of returning to Nature, our inherent roots.

The violent machines programmed to destroy them bored through the Earth’s mantle and entered the pod via the ceiling. The humans, despite their valiant efforts, could not stop them from entering. And once they did, the machines duplicated and spread everywhere, destroying everything in their path.

This, is how I began perceiving these phenomena in these indigenous villages. For once the high power electricity — the satellite dishes, the programming, etc. — and the top-down government policies (such as land-use regulations) arrive, then the culture’s socio-fabric becomes affected from the inside-out. This essentially creates an ethnocidal entropy. And I’m not saying that advances in technology and modernity are inherently bad. I’m merely suggesting that what is considered “traditional” and what is deemed “modern” cannot entirely co-exist.

This said, I maintain that there are socially binding commonalities that all humans share. These are our intrinsic needs to be loved and accepted, to be accepting and loving, as well as our necessity for having a nourishing natural environment that includes familial and community connections. This, is a form of ‘paradise.’ Perhaps all humans, deep-down, are seeking this. For isn’t this what all living creatures on this planet are about? Are we all not powered by the same energy? Is the ‘natural’ not our ‘nature?’

Roots of Societal Transformation…

Placing these phenomena even further into the context of Nam Bor Noi village, Tior’s community is encompassed by nine other Karen villages. They all constitute a lowland Karen settlement area called, Phabat Huaytom, with a total population of about 13,000 people. Like its surrounding Thai lowlands counterparts, it is as well underway to succumbing traditional culture to a modernizing trend. This is transforming ways in which they interact with each other and with their surrounding environment.

Tior said that in the early 1970s there were four Karen elders who were seeking “a healthier way of life” away from hardship and opium addiction. They held Kru Ba Wong’s Buddhist teachings in high esteem and pioneered a new path by pilgrimaging from the highlands to Phabat Huaytom in order to learn from the sage.

“Nearly fifty years ago, I lived high in the mountains,” said Kabuwa, 84, from a hut-like structure placed in the middle of a watery and verdant rice field. He is one of those first four pioneers who came to this area. “My life wasn’t comfortable (up in the mountains). The transportation wasn’t good. I had to walk on the steep and mountainous slopes, go up and down. It wasn’t good. But it was easy to hunt and find wild food.

“I was inspired to change my lifestyle for Kru Ba Wong, the great Buddhist monk who visited my village many times,” added Kabuwa. “He brought with him many wise teachings. He taught about the Buddhist code of ethics and the five precepts (i.e., don’t steal, commit adultery, lie, drink alcohol, or harm animals).”

Kabuwa explained that when Kru Ba Wong invited him, and those in other villagers, to come live in Phabat Huaytom, “I left my highland home and followed him. The only criteria for living here was that I had to accept and maintain the regulation of strictly following Buddhist principles. I also had to become a vegetarian. Despite these lifestyle changes, my life here remains much more comfortable than it was while I was living in the jungle forest.”

When Kabuwa arrived at Phabat Huaytom, there were only two houses built. Soon after his arrival, however, many Karen began migrating here. Infrastructural development had also expanded.

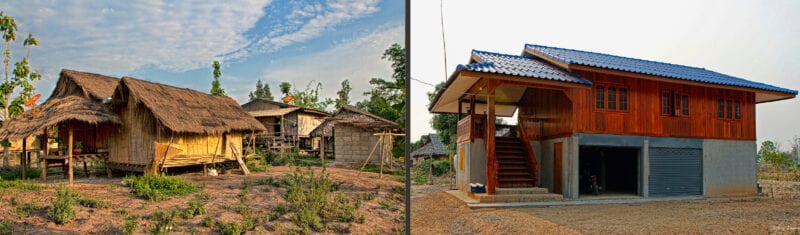

“We all came here to follow Kru Ba Wong, to make merit, to follow his teachings,” said Kabuwa. “When I moved here, there was abundant shading from large trees, unlike nowadays,” he said. “The houses were constructed of bamboo and grass, Karen style…Everyone lived in harmony. We were sharing, not selling things like we do today.”

Kabuwa revealed that the most significant limitation at that time was water scarcity. There was only one water source, the sacred well located at the Buddhist temple that Kru Ba Wong had initiated. “The water well was a small pot, but it could support all of us villagers, as a community,” said Kabuwa. “This is why we call it a sacred well.”

Kabuwa recalled that there wasn’t enough water available at that time to grow the number of vegetables required for the expanding community, so they (perhaps for the first time in their life) had to buy food from the local markets being established.

“To pay for this, I worked in the fields for two to five Thai baht (less than US$.15) per day,” said Kabuwa. “I became firmer about my working rate and eventually received ten baht per day for my labor. I gave half of it to the temple, for making merit to Kru Ba Wong.”

Kabuwa shared that Kru Ba Wang was a wise man who had a good plan and created a residential zoning system as well. “The roads here were made from dirt and lava rock,” said Kabuwa. “We (Karen) hand-built the roads, while the Thai people watched us construct them.

Back to the Humanity Basics…

Just thirty years ago, all villagers in Phabat Huaytom still lived traditionally like those in Nam Bor Noi, and as Thailand’s hilltribe people have for generations. This has near totally vanished.

“In the past, we had no modern technology,” said Kabuwa. “We hand-washed our clothing. We used organic materials such as roots and charcoal to clean our teeth. All of our food was cooked using a wood-fueled fire, and we used candles for lighting our homes. We walked everywhere. Only the wealthier people could afford a bicycle. Still, everyone was in-harmony, unlike nowadays…Everything has to be purchased now. People are more selfish, and they buy more things.”

“Thirty years ago, many outsiders, tourists from within Thailand and from other parts of the world, came here to observe our traditional ways of life,” said Kabuwa. “They brought foreign objects, and ideas. This changed us. It transformed our traditional ways of life.”

Kabuwa revealed that things really began to change here about ten years ago when the road was changed from dirt to tar. “This brought the outside world to us even more,” explained Kabuwa. “In some ways, things did change for the better after Kru Ba Wong asked King Rama IX to bring academics here to teach us what plants were best suited for here.”

The King also agreed to Kru Ba Wong’s request to have all villagers abstain from being drafted into the military, due to their strict Buddhist beliefs. His Majesty also helped develop reservoir and irrigation projects which, for the past twelve years, has allowed the village to begin to grow rice.

“There used to be one man here who could teach Karen writing, but now he is blind,” said Kabuwa. “We proposed these teachings be part of the curriculum offered in the local Thai school. However, this idea was rejected. We were told that if we are to be Thai then we must learn Thai. We are not Thai!”

What Can Be Done to Preserve These Ways of Life?

“Nowadays, we can and do maintain the traditional Karen ways of life,” said Kabuwa. “We still, for the most part, keep the Buddhist precepts. We still speak Karen with each other. We still weave and often wear our traditional clothing. Our houses still have no fences around them; we welcome our neighbors.

“Nowadays, we can and do maintain the traditional Karen ways of life,” said Kabuwa. “We still, for the most part, keep the Buddhist precepts. We still speak Karen with each other. We still weave and often wear our traditional clothing. Our houses still have no fences around them; we welcome our neighbors.

“We aren’t forcing anyone living here to do this,” he added. “Everyone is doing it by himself or herself. I believe that by people staying together like this, we can keep ourselves together through community connection.”

Kabuwa is concerned about the younger generations. He said that the middle-aged adults and the elderly understand the importance of the village’s cultural and religious beliefs and convictions; however, he fears that such customs are not being taught or passed on to the young.

Tior admitted that he also does not expect that the newer generations will preserve this culture. “However, once you’ve been in this environment, it will be with you forever,” said Tior. “Because the younger generations here have lived like this, it will be with them forever…If we take care of our children, equip them, then we will protect our culture.”

Kabuwa was asked if he had a specific message that he wanted to share with Thailand’s hilltribe people, and with the world overall.

“I don’t know how much longer I will be alive,” said Kabuwa. “I don’t know what will happen here once I am gone. I don’t know if their lives will have more suffering, how much they will be so busy. It’s not like in the past. I know I feel sad, if they don’t keep a simple life like in the past.

“I want the Karen to come back and keep our traditional ways of life,” he added. “Don’t leave it! Don’t see capitalism, the outside world, as more important than our traditional ways of life! Our way of life is simple, not busy like those people in the city. Keep the good relationships that we have with each other…

“I want to say to the Karen people that if you have lost your way, please come back.”

* * *

Author and Acknowledgements:

Jeffrey Warner is a civil journalist and documentarian-storyteller. He focuses primarily on social change patterns, resilience, and building social capital. Jeffrey, from the USA, has for a decade been living in northern Thailand. He’s been studying and documenting how some of the region’s marginalized people, particularly ethnic indigenous communities, are being social-ecologically impacted by development phenomena. What does this potentially mean for humankind? … Jeffrey’s dissertation-length thesis about this topic, “The ‘De’ of Development,” can be viewed here. … You can also view his book, “Indigenous Voices: Glimpses into the Margins of Modern Development.”

Jeffrey feels deep gratitude for Tanya Promburom, for making this overall research work possible by facilitating years of village visits, for the brilliant translation work, and for the overall personal and professional support.

*A briefer version of this article was published in Chiang Mai Citylife magazine on August 21, 2020.

Leave A Comment