Interview with author, Jeffrey Warner; by Elena Reikheim

(note: raw transcription)

[Interviewer: So, what is this all about?]

This has all been a personal journey from the start, really. It started out when I moved to Chiang Mai three years ago and I saw this place as this big city small town haven. It at first felt to me like the small town that I come from, yet it had many different things about it that I could reference from my past travels. There are motes, things like that; I have been around Europe. There is a huge Buddha placed on top of the mountain here in Chiang Mai. This reminded of being in Brazil, seeing Christ the Redeemer. There are certain unfinished buildings here that remind me of my times living in war-torn Bosnia.

(Being from Minnesota in the U.S.A.) I was used to being near water; now I was here (in Chiang Mai) living at the base of a mountain. I interpreted this being near the mountain as sort of a symbol of grounding instead of being like water, movement, like I had always been living. This was a time for me to ground, to sit in one spot for once, instead of always going here and there and everywhere. So I saw these environmental symbols as a representation of my spiritual journey, and what I am supposed to do with my life, now. I knew (being in Chiang Mai) that I was where I am supposed to be — getting away from, in many ways, the modern world of being in America, the constant bombardment of media messages. This is a big story. I don’t want to get too convoluted here in what I am saying.

Seeing the way Chiang Mai was changing more and more, I started to view development in a different way, because where I come from development is considered a very positive thing. When someone builds a garage or a new house, it is viewed as a very positive thing. ‘Oh, Joey is doing well for himself. Ya know. Good for him. He’s putting up a new pole barn. Finally he is going to have a place to put his four-wheelers,’ something like that. It’s a place for Joey to put his stuff. Good for him. In American society, having more stuff is a sign of progress.

In contrast to how I grew up, I started seeing this development here in Chiang Mai as the opposite way of progress. I saw it as a devolvement, not a development — a devolvement of the human species in general because you are taking these places like these beautiful rolling hills and this beautiful city and places like rice paddies and filling them in with concrete and building condominium complexes. It began to drive me crazy, seeing this, more and more.

As Chiang Mai has become more of a city, I began having more rural experiences through someone close to me, as she and I were going on these adventures in the jungle. I was taking this motorcycle that was made for the city up into the jungle, looking for waterfalls. This all started by looking for new waterfalls to find! And then I started falling in love with verdant rice fields, the expansive grounds and the nature that is northern Thailand — the energy that I was getting from nature and learning what real Thailand is about, which is about nature. Thailand is not about the city.

I started having a real problem with the way things were de-veloping and starting philosophically looking into this concept of what is good or bad, if good or bad even exists. This has been a personal journal basically of trying to seek peace, to seek nature, as I was growing in my spiritual path.

I came to Chiang Mai believing I could do anything I want, that this place is unbelievable, that I can manifest anything I want to create. I was lonely and doing different things with my personal life. However, I was growing at such an accelerated rate on a spiritual level that ironically as I was growing spiritually, I wanted to withdrawal from mainstream society all together. I found being in the nature of Thailand as this place where my spirit felt like it belongs. And anytime I came back to the city, it began affecting me in very profound ways, mostly negatively.

As I was trying to get out more and more into these different communities, basically getting out into the jungle, I started to see a different side of life, and wanting to withdrawal, a desire to remove myself from mainstream society. I didn’t want to become a hermit. I just wanted to withdraw back to my root system, back to a point of innocence. And this point of innocence is my root, who I am at my core, and this nature. Nature is my God. This is where I comfortable. [I AM ACTUALLY A LIVING REPRESENTATION OF A FRAGMENTED SPECIES HERE.]

So I started having these adventures, different things that were manifesting, meeting different people. Being here as a journalist, I began wondering why I am here. This was also after working with people on the Burmese border who were living on the rubbish dump, seeing people living in this horrible environment. However, this journey has never been about them being in that environment. It was always about the nature within those environments – the beauty I see within this cancer that we have created with modernization. This is the way I see it.

I hadn’t started working with the hill tribes yet. This is the thing. There are two stories, and I don’t know what the timing is.

One morning, my girlfriend and I went to find a waterfall in the jungle. We never found the waterfall, but we did find this hill tribe village. This may be the first village I went to. The point is that I got out of the city and saw all of this nature and everything, climbing up the mountain looking for this waterfall. We ended up in the middle of this White Karen hill tribe village I felt so free and so happy. I didn’t know what was going on there. I just felt this inner freedom, and when I came back down into the city, and I felt the way that I feel when I am in city, which is ill, literally ill – not because I am saying “I hate this!” I don’t know exactly what it is. I started seeing the contrast between the city and hill tribe environment more and started wanting to seek out these hill tribe environments.

I also started saying that, “We say that globalization must happen. But in an hour period of time, I just went from a city environment to up there where they are thriving. They have crops, clean water, homes. They have everything. No electricity. They had solar power, but that’s it. They had a waterfall. Everything. They seemed happy. I sat and watched them play games together. I felt great.

So I began asking, “Why is it that globalization has to happen? Why are people telling me it has to happen? Why are people saying this? I am going to prove to you with 12 photographs and one story that it does not have to happen. It is a myth.” This is when my real interest began building.

This also began when a friend of mine who is a journalist working with a woman who is an anthropologist who did all of her research in the first village I went to, Doi Mod. I went there with them because they were going to do some work at a “bamboo school,” where one day per week, they teach traditional Lahu schooling. It’s not a well-funded place. I went there, and for the first time was really inside of a village environment, so everything was new to me.

What compelled me was there was this old man sitting in this hut teaching all these children about these herbs, all this stuff he dug out from jungle, because no other traditional medicine person has stepped up to the plate to do it. And won’t because of what I learned a little bit about at the time. They have motorcycles now. They go to the city. I really didn’t know anything. All I knew is that I felt a very deep calling to preserve that, to preserve, to do a documentary or something, to show that this is happening here – to conserve this man’s knowledge. I felt that it was the most important thing that should be happening in the world right now, conserve this man’s knowledge, to preserve it.

And being exposed to these different things throughout the three total times I had been in this village. Another time I went back with another person and saw different things, sat around a fire, cooked frogs, drank rice wine under the moonlight and different stuff, living wildly. It was totally unplanned. It’s just what they do at night

[Interviewer: What were your feelings about that? Actually, you probably felt pretty peaceful. You felt back to the roots, calm. But at the same time, you were seeing that the villages were starting to develop. So, this didn’t effect your feelings?]

At the time, I wasn’t thinking about development specifically. I was only thinking about wanting to come and live in a place like this, and live the way human beings perhaps should. At the time, I had been away from home (where I come from) for so long that I had lost track of root system. I was losing myself. My brain, my mind, was cracking. I was fragmented, in a sense, which is actually an analogy for the human species, generally speaking. Everything about me that I had grown an ego around, all of my belief systems were cracking. So I was seeking out some familial environment that I felt was pure.

And at the time, I was romanticizing the village life. So I wanted to live and learn in there. I remember talking to a village man and asking him, “Jekadte. Do you mind if I come back here and learn how to live?” He giggled. I stopped, turned around and got really close to his face and said, “Do you think I am kidding you?” He took it in and said, “No.”

I saw these people at the time as living in nature, with their natural environment. And I wanted to get in connection with this.

(Interviewer: To find yourself, right; to get back to yourself.)

Basically. And also it was just a way of life that at that time I just didn’t understand. So as I was being exposed to more and more things about what was going on around them. I had never before seen them cooking food over a fire or charcoal (comprised of chunks of wood previously burned and then extinguished for later use), collecting food from the jungle. I was being asked to go into the jungle. They were going to make me a knife. Different things, seeing people living in this tribal environment. I had never seen anything like this before, so everything was completely new.

So I had been there several times and seen different things. Okay. They were going to develop the village this way and that. I learned about how NGOs were coming in. I learned about how the Christian missionaries had their effect on the village, etc. However, everything was based just on observation. It was never based on, ‘Oh. Look at that satellite dish!’ I wasn’t looking for those kinds of things.

[Interviewer: But you say that as you went there and kept going, learning new things, this made you feel good. Which direction did it take after that as you began learning more and more? Did you suddenly see that they are struggling with this and that? What is the direction you went to after this?]

Well, this is what I am trying to process right now. It’s been one long journey. So all I can do for you right now is tell a story, based on what comes to mind. There is probably a lot more to it that I don’t even know at this point.

All I know is that when I was back in Thai culture, I started seeing other things as well. I started seeing the Thai traditional houses and the condominium complexes that were being built and started seeing the dissolving of culture and started talking with people; for example, a man who had been driving around a horse and cart taxi his entire life and how he felt about the changes around him as he is now being passed on the street by trolley trains, speeding cars and motorbikes.

I began wanting to take as many photographs as possible of a culture that I saw was dissolving and being replaced with modern technology – seeing a better, more pure way of living being replaced with this Matrix, this machine world. This began expanding my mind. I started seeing, developing, this concept of the world, viewing it as though the movie, the Matrix. Mostly like the third movie.

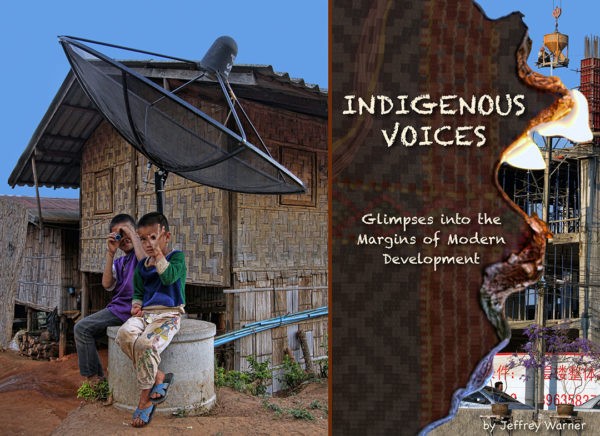

I’m going to go back in time. I saw a television set once while in a village. And started seeing it more and more as the Matrix movie when the remaining members of the human race are at the center of the earth, in Zion, which is all symbolic because people had to retreat back to nature, their core. In the movie, the machine drills were puncturing through the protective dome above them. The drills break through, hit the ground and explode into many machines that take everyone out. And this is how I started seeing the television set. Actually, I started noticing satellites in the different villages I was visiting as this – pointing off into the sky as that way of the Matrix entering the village cultures. Because once the satellite comes, the outside world comes, the programming. At first, I was just thinking about the satellite. I didn’t know about the electricity at the time. I didn’t think about this, or the roads or anything. This was all a learning process. I only saw satellite dishes. So I started taking pictures of satellite dishes, connected to wooden houses. I thought about how ridiculous this looks. I didn’t know anything at the time about how this technology was affecting villagers’ relationships with each other. I only started seeing this development as only technology. So I started seeking out these different hill tribe environments.

[Interviewer Why? Why did you go back? What were you searching for?]

I just found myself doing this, almost effortlessly. I wasn’t trying to seek out this village or that village. I wanted to be a photographer for an NGO or something like that. However, for some reason I just ended up being in these different hill tribe villages.

So the next village I ended up in: I met this guy while I was in tee-pee during a Japanese music festival in the middle of the jungle and at the center of a volcano. He was working for an NGO and learned that I was a photojournalist, and he wanted someone to do a documentary. He said come to Chang Dao and try us out. There is another village. Go there and photograph an event for us. So I did.

And this village was completely different than the ones I had previously been. There was no electricity. It was just flat. I knew very little about it or them. All I knew is they were from Burma and the police had come in beaten them up, taken them out of there; they had been removed many times. They had experienced a lot of hardship. So this when I began learning about villagers’ hardships a little bit. Instead of romanticizing their way of life, I began seeing snot coming out of children’s noses and people coughing and seeing more of the harsh way of their life, but still not knowing anything. This was the first time I had been in a village where there is no electricity. As the sun went down, I was wowed at how the feel of the village changed once the sun went down, etc.

What started happening is while working in that village, there were professors there from the Center for Ethnic Studies and Development (Chiang Mai University). They were watching me work. I was taking photographs and taking video at the same time, running around and going back and forth between the two mediums. They asked me to meet with them at the university. I them showed them my other word I did on Burmese border, which also has to do with development.

This work always has to do with coming back to nature. It always has to do with the base of humanity. It always has to do with the goodness within these terrible situation.

The professors later invited me to go to another village with them called Hin Lad Nai. This is a village that they say is completely undeveloped. However, now that I look at the photographs two years later, no; there is development there. It’s just that it’s being kept in a certain way, like cultural preservation.

I was then learning more about what is happening in-terms of the Thai government, how it views hill tribe people. I heard stories from this one young villager about how the forestry department is becoming involved with these people. He told the story about how the government told the villagers that they had to leave their highland homes. They moved but there was nothing for them down there, no food or water for them. So they went back up to their homes and then the military (supposedly) showed up in the middle of the night helicopters and torched the village. The youth was crying while telling this story.

I started learning more about different things. This village supposedly rejected the one million baht loan bribe from the government to development. ‘Oh. We’ll come in and give you solar power. We’ll help you with your roads. You can grow some cash crops,’ things like this. So my knowledge was just starting to grow a bit more. And it wasn’t until I was in that village and captured a photographs of two guys who looked just miserable. This is when I started to truly change my view toward the potential of this romantic way of life that they live.

[Interviewer: What do you mean? You didn’t see it as romantic anymore?]

No. because I began seeing the reality of it. It’s sort of like when you first move to Thailand. You move here and think this place is this dreamy carnival, and then you start to see the layers.

So, after this experience at Hin Lad Nai, I went back to the States. I was pretty much broken as a human being. It was too much. It was going through a necessary personal process. However, when I returned home I got back to my root system. When I returned once again to Thailand, I felt really good and got involved in good community here. I met some Christians that were from a Karen village. So I ended up in this Karen village, learning about a whole other side of this tribal life. I started learning about family and their work life.

Then I started learning about cash crops and the corn. I started learning about what it felt like to be in a natural village at night time with no street lights – waking up in the morning after actually being able to sleep. I hadn’t slept in such a long time. So, I was learning more and actually feeling the warmth of the family part of this and how these people live out in this beautiful environment.

It was so natural and pristine. But also talking with the people I was with. Every time my village friend and I would have to return to the city, we would complain and couldn’t wait to go back to the village together. We both wanted to be back in the village. But he had to be in the city in order to make money to support his children. So I began learning more about these cash crops, which is any crop you grow for money. This village (most all villages) used to be a self-sustaining community even 20-30 years ago. And then the government came and convinced them that it is a good idea that they grow these cash crops, so they can make money – basically so that they can put their children in Thai schools! Which is the very thing that basically turns villagers’ cultures inside out. But they do it because they think it’s a good idea. I was told that the Karen in this village (Mae Lu) actually do it so they can properly work with the government and not be taken advantage of. It’s for protection.

[Interviewer: Yeah. But they have to. If not, the children could not receive an education.]

Yeah. But their education is all Thai based. So everything has been switched in-terms of their education. Maybe they have one day per week of learning about their own culture, and six days per week of Thai education. So what does this say about the dynamic of what is really happening here? Now their native culture has become second to another culture.

So I began gaining more insight into how villagers live, having more and more experience being in these villages. Now I mostly started becoming interested in the technology. Look at the technology that is infiltrating these villages – electricity, television, street lights, things like this. Then I started learning a little about villagers’ relationships and wanting to do something.

[What do you mean, learning about the relationships?]

Well, I started learning that development isn’t about technology, at all. It’s about how this technology changes people’s relationships with each other. It’s about how the infrastructure changes the way people survive. It’s about a global market economy.

I learned in this journey while back in Doi Mod, the first village, that how development “is done” is through the economy. But I didn’t understand this at the time. This is how these cultures are taken out, through the use of economy. It becomes impossible for them to survive on their own anymore, completely in nature. Basically, government legislation is created that makes it so that tribal people have to submit to a certain economy.

I began paralleling this knowledge with what I learned throughout my world travels, particularly regarding the United States. This is when the whole idea about development began to really expand in my mind, when I began contrasting the little I know about what the U.S. Government did back in the States with the Jim Crow Laws for example where race (and ethnic minority groups) was created in the United States through legislation. Race doesn’t even exist. At a genetic level, race does not really exist.

It was actually created via government institutions to essentially maintain a society’s socioeconomic hierarchy. You create things like “African American” and “Chinese.” And the cash crops they know how to maintain and perhaps sell in order to make a living play a role in this. For example, if you make marijuana illegal, it it’s a cash crop for Mexicans trying to make a go of life in America, it takes them out, and puts them in to the prison system as well. So they can never really climb up the social hierarchy. With the Chinese in the States, it was the cocaine. Here in Thailand, it was the opium.

So, ethnic minorities can no longer survive. They have to have cash crops like tea, vegetables, so that they have to make money to buy things. They can no longer be an independent society. So, my point is that I started paralleling what is happening here with what has happened in the United States, including with the Native Americans, and started posing more questions.

All of these are questions. And the questions are, Hmm. Look how the Native Americans were taken out. Look at how the capitalists took out people’s small rural farms in America. They did it through big industry, through global markets, through economy. They are doing the same thing here in Thailand (and the rest of the developing world).

If, for example, you take the world economy and flood it with the corn from America, this drops the market value. So you get the small local rice farmer here in Thailand (or the villager living in the mountains), who can’t afford to be independent from large corporations or government subsidies any longer because the selling price is now so low that he cannot survive independently. It perhaps forces him to sell his farm and move to the city and work for large corporations. I suspect that a similar thing is happening here in Thailand.

The way to do this is to homogenize people’s cultures, make everyone essentially the same. So I started learning more and more about what is happening to hill tribe people, and trying to find the possible connections between how my home country was developed, and now that I am in this developing part of the world, are the same development strategies being implemented? Is it happening to the Thais? And now is it happening to the hill tribe people as well, who for the most part aren’t even considered human beings in mainstream Thai culture (“They’re called, ‘the other people.’)

So this is when all of my experiences began developing more and more in to a deep curiosity, a passion to try and parallel these two realities between where I come from and where I am and understand the developing world.

So, I began ending up in other hill tribe villages, learning more knowledge. I was approached by CMU to do a documentary on the Hin Lad Nai village. However, at the time I had already built up this curiosity about development and what is happening to hill tribe people.

I wanted to know if it is true that what is happening here in Thailand is the same thing that has already happened in the States, for example. Because Europe has thousands of years of evolution there, right? And I don’t know enough about Europe to pull from any knowledge. I’m not even going to try. This just because more of a curiosity.

[Interviewer: You wanted to know in order to make a difference, to change something?]

I’m not sure. I just wanted to understand, and this has evolved into something more and more. Every time I go to another village, I learn more.

This isn’t so much about the hill tribe environment, per say. It’s about looking into what I view as the core of humanity, where people within short distances of urban modern environments are still living off from the land.

Okay. I am on the periphery of globalization. I call it this because modern development is like this snake, this growth going around the earth. Where I come from is the tail. And now here in Thailand, there are these people who are trying to live this traditional way of life, and in some ways are, as all human beings once did. And they are slowly being engulfed by this world market system.

So, I see this as, ‘Hey. If we can get in now and look at these people, while the elders for example are still alive, and their cultures remain intact. And if I can talk to someone who is 80 years old who knows little or nothing about the modern world. And at the same time I can talk to a teenager who is excited about some Koren hip-hop artist at the same time, wow; how much insight into what is really happening can we all attain?

The theory is that if I go into these environments before they are completely transitioned into, well, being machines basically, like the rest of us, subjected to this economic slave system, which is what it is, this slave market system that turns us all into corporate slaves; we’re not free, any of us. The only time we are free is when we live within the limitation of our resources. Right?

So, these villagers are slowly losing their freedom. And I thought their freedom intact. However, once I went into the Doi Pu Muen village, this is where I truly learned that it is the market system that is taking them out. However, their already gone. Their traditional culture is gone.

Anyway, the theory is that if we can analyze these environments in their current state, then we can perhaps apply this to what has happened to the entire developed world. We can learn from this and perhaps it will stimulate all of us in the world to at least take a moment’s pause and take a look at ourselves.

[Interviewer: So you wanted to get there before the market system put its hand over them, and you realized that it already happened, kind of?]

Yeah. As I learned, I realized that they for most part are already gone. Their traditional culture is already finished. You cannot have modern culture and traditional culture at the same time. Modern is modern.

So what has happened is the government has essentially removed their ability to live as they traditionally know how. For instance, the Lahu are hunters and gatherers. They fish, hunt furry animals, grow their own upland rice, collect their own food from the forest. They didn’t need a city. But now they do need the city. Because through the government legislation, now they can’t cut the forest anymore. They cannot live like Lahu people; impossible. So they are being pulled into a homogenizing world culture.

[So you said, ‘damn it; I’m too late.’ So what you tried to do is look at modernization has already influence them.’]

I’ve never came to a conclusion that I am too late. I just came to the realization while there that the tribes I was working with are basically just in shock. They are being bombarded by and with this system. But at the same time, they are perpetuating their own destruction. They don’t know how to work with their kids now who are wearing blue jeans and purple hair, walking around the village drunk. The middle-aged people want to preserve the culture; yet don’t really know how to. They only know what they’ve been taught. The older people are like, ‘Who are you?’ to the youngsters. And the people in their 30s are like ‘Oh. I want a TV too!’ Because they are still kinda like kids themselves.

The young village kids are now having the same pressure that we have in the West, especially regarding education and ‘Who (what) are you going to be when you grow up?’

So they are essentially turning into Westernized people. They are turning into the Matrix system. But they are kind of in this in-between point.

But this whole thing for me has really been a personal journey of finding a place of peace to a deep intellectual exploration and a sociological endeavor to try to figure out what is happening here and how it can be applied to the entire human species. Because I see the world as a global community. So if we can look at ‘them,’ and say ‘Look at what is happening to, them,’ then this is the same thing that is happening to everybody else on Planet Earth.

This isn’t about what is exactly happening to the tribal cultures. It’s about the base culture of human beings. Because we are tribal by nature. Right? We’re not supposed to live in communities any larger than like 300 people. Do you see two million deer or elephants living in the same area? No. It’s completely unnatural.

(Interviewer: In the beginning, you saw the village as romantic, then you started asking questions and seeing the struggle of the people, and then you saw why and that the culture is already going away. How do you feel about it now? How do you feel about the villages. You say that you still feel free, some kind of purity when you are in the villages. So, the villages can’t be that much effected, now, because otherwise you wouldn’t feel this way.)

Well, when the other night I went in to a village, and I go in to a little hut, with like 30 children, all having candles and wearing their traditional dress, and this isn’t some tourist stage show, and they are in there with an old man dressed in white who had come out earlier and a bird came down from a tree and landed on his shoulder. And these people are eating vegetarian food, and carry with them a philosophy related to this. And they are doing this ceremony together, and we all sat together and turned the same direction and meditated together for 10 minutes. And all of the other villages surrounding this village are developing, with their big houses and electricity. But not this village, because of a belief system and a hermit monk who came in and set the stage for this natural way of life, I realized that they don’t need help, at all. They are not the ones who need help. We living in this modern world are the ones who need help.

Leave them alone, and they will be okay. Stay out of their villages. The fact of the matter is that I should not be walking around that village clad in blue jeans and my checkered shirt and my big fancy expensive camera. I did harm to them. I put thoughts into those children’s minds that they didn’t have before I went in there. So while I am supposedly preserving, I am also destroying at the same time. They are pure.

And going into these villages and seeing these different things isn’t so much about whether the village is developed or not. It’s about their thinking processes and how they have learned to justify the materialism around them as a way of simplifying their life, and making their life supposedly more convenient.

[Interviewer: But there are also villagers’ voices saying different things.]

Yes, based on varying degrees. There is one village that I was in that is somewhat living their traditional way of life. However, the Hmong village I went to is totally gone. They are mass producing tote bags using electric sewing machines. They have a concrete house, tile flooring, hot water, satellite television, a washing machine and a gas stove. They were animists two years ago. Now they have a Buddhist spirit house placed in front of their house. They’re gone. And they admit it. Yet, they think their culture is still intact because they wear green and black clothing. It’s gone. It’s just a stage show now.

***

So this has gone from a personal endeavor to find people to an intellectual journey to find understanding. It’s sort of like going from ‘happy is the man who finds wisdom and gains understanding’ to now it’s a matter of creating something that literally shows people what is happening to these villagers from the inside based on their relationships and the way that they think. If this can be portrayed in a very clear message, it has potential to apply to anywhere in the world. This is a global issue.

[Interviewer: It’s a portrait of what has already happened to people in the West because we have already been at that point. At some stage. It’s like the snake. It’s already eaten. This shows us what happened to us a long time ago and how things could have been.]

Right. People in the modern world are already long gone in the Western world. It’s so far developed over there, that it is fully the way of life. It feels comfortable there, because it’s good. If neighbor Joey puts up that nice garage, you can come over and relish in the nice garage. That’s seen as a sign of progress.

I don’t see people losing their traditional culture as a sign of progress, at all. If you take the definition of the word ‘development,’ which is to take existing resources, converting land, and building infrastructure using those resources for a different purpose; this is development.

However, with this project, I want to focus on the ‘de’ of development. I see that we devolving as a species. We are actually taking something away. We look at develop as though something that we are building. However, actually look at the word. Break it up into its individual parts. ‘De’ means reversal or take away. ‘Velope’ means encompass or surround something. So why are we are viewing developing as something referring to creating? The word itself essentially means to take away.

Let’s look at the word ‘civilized.’ It means to bring a place or people to a stage of social and moral development considered to be more advanced.

So someone can try to tell me that going from a point of being in community with each other and living in-balance with nature, living in-balance with each other, having community and respecting your elders and eating good food and having good food and water, from being independent to this modern, synthetic world and the way we treat each other – the institutions, the crime and pollution and the individualism and the materialism, that anybody in the world would say that this is bringing people to a place of social, cultural and moral development? This is a paradox.

People living in these villages are being called ‘less civilized.?!’ They aren’t less civilized! Pigeons are more civilized than most human beings. Look at the definitions.

[Interviewer: But as you saw the villages, you learned that it isn’t like this, right – not romantic, that they’ve turned into something; bad, modernized. You just described the village, regarding respect for others and natural food. But this is also not true anymore, maybe this natural village you went to the other day with the ceremony. But the others are turning into the same things already, or not?]

Well, villagers in many ways suffer. I’m not saying that what I have seen is that they they live these dreamy lives. It’s a very hard life. I can see why they told me that a bamboo hut is so cold and dusty, that they want a concrete house, a hot shower.

So who are we to say that they shouldn’t have electricity, or should live this way or that way, that they don’t deserve these comforts. The point is that these comforts are altering their relationships with each other. But for the most part, people who live in these villages work hard. However, they work as though more in-balance with their land.

Reverencing the first village I was in: I was feeling so fragmented as a person, being so far from the area I come from across the world. I said to Jekadte who was standing there, looking to me as though this big tree root. I said, ‘How does it feel to feel connected with your land, to feel like you have a home, connected with the earth and the roots around you.’ He sat there, almost welling up in tears, and said, ‘It’s beautiful.’

So this has been a journey of someone, myself, away from home, whatever you want to call home – home within my home, whatever this is. This is the evolution of a human being going into these different environments and seeing the parallelism between how people live here on the opposite side of the planet from where I originally come from. What is happening to them? How is the world economic system effecting, them? And how does this really boil down to nature and the way human beings fundamentally feel called to live. What is happening to these hill tribe people is what has already happened to the modernized world.

It’s a huge paradox. We create this stuff around us – these cities! I just don’t understand. It’s an illness of the human species.

[Interviewer: So you’re still saying that those people in the villages, that it is more comfortable for them to have a concrete house and not a bamboo hut, to have a hot shower and not pour water on themselves while in the street. So, don’t you think a little bit of modernization might be okay?]

Well, that’s not for me to decide what is or isn’t okay. All I know is went and I sat with a villager, and purposefully brought with to the village a bag full of candles because I knew that the family only had electricity for two months and she had grown up using candles once the sun set, so I wanted to set the stage for an interview, and she pretty much fell asleep to the candlelight.

So you tell me that just because she has electricity and color television, and she tells me that she likes it, does she really like it? When she told me ‘Now I am lazy; now I have to be like my neighbors who also have a television; now we don’t sit around the fire anymore and talk; we watch television. Before I used to sit around candles. Yeah. They were expensive and stuff, but now I sit around the television and go to bed late, and now I wake up tired.’

Tell me this is good, really. So whether they want to think this development is good or not, with the onset of the electron into their world, it’s so completely unnatural, it’s no longer traditional culture; it’s modern. You cannot have both. They are trying to have both. Because at one point their traditional was modern, right? However, you cannot have modern technology and fully maintain traditional culture; it’s impossible, in my opinion. The related lifestyles are completely different.

[You’ve maybe told everything that is necessary. Did you forget something?]

I don’t know.

The driving force behind this thing, whatever this thing has been, this whole adventure, has been to get to the core, to go to core of the human species, of humanity. This story that I’ve given you is just a framework.

This isn’t just about hill tribes, right? It’s also been about Thai culture as well and global community. This is about posing questions, asking questions, coming up with different theories, trying to figure out, ‘What is happening on this planet?! What is happening? Let’s take a look at ourselves? What are we doing?’ Everybody knows it.

This project isn’t about hill tribe people. It’s about humans. And these hill tribe people represent the core of humanity.

[I try to listen to your words, seeing how your stops during this journey, how your thinking has changed. Because through this, I know what the book is supposed to do with people, to be at different points, to in the end get to the point of where you are now.]

Yeah. I want them to be confused somewhat, throughout. Are they going to be able to go through the physical journey? No. I have 6,000 photographs.

I would like to know the journey myself. I’ve been on the journey, but I’d like to know where I have been as well. This is a story. It is the framework.

You know what this is? This is a one and half year-long memoir. It’s a memoir and an exploration into really the depths of what is happening to the human species. There is way more going on here than just some stories and a few photographs. This is what it’s really about.

[This should just take them on a journey, to get them to ask questions. And then you can keep going with your career, have discussions about this. Then more will come.]

Yes. You can explain things when you understand them yourself. This isn’t about taking photographs and running around in pretty hill tribe villages, for me. It’s not. It’s much much deeper than that. This is just the first time I have talked about this.

The questions I am asking are also about my own questions. Of course I want to know what people have to say. I was in some of these interviews and choking up with tears because I realized that these people are just in shock. What is happening to them is form of ethnic genocide.

This is what they are doing to these beautiful tribal cultures, through legislation. It’s ethnic genocide; the same as they did in the States as well with Native Americans, as I said. However, the Native Americans have maintained their culture as much as they could. Yeah. They’ve been under 100 years of assault, been out on reservations, have many sociological problems (alcoholism, drugs; same as in the hill tribes now).

But they try. And they have retreated as much as they possible can. And now as the white man’s culture crumbles, as our school systems for example can no longer function, their systems in some ways are thriving.

What will happen to the tribal people here in Thailand? I don’t know. They’re just letting themselves go in a sense. There is not much they can do.

[Well, maybe they see, ‘Ooh. I have a hot shower. That’s comfortable.’ So why would you reject this? They don’t have your experience of already experiencing modernization and going to the hill tribe villages and feeling peace. So how can know that this modernization will make them sick, at some point?]

They don’t. They don’t understand. How could they? And I have seen it just through talking with even a few people. The people in the Hmong village are just gone. Whish. So they are at a point. Geez. I don’t even want to use the word advanced. A devolved state, okay?! Even though it has moved forward in some way, it is in a devolved state from the people who are in the Lahu villages (I went to). The people in the Hmong village are now saying what the people in the Lahu village will maybe be saying five years from now, or ten years from now.

They have learned to accept their reality. And they have learned to accept their reality because they have to. They have no choice. They have no choice any longer. They are being systematically taken out.

They don’t have a choice. But the core, if you want to use the word sickness, of this capitalism, this ‘Be one up of the Jones” is the American term for it, if you look at your neighbor and see that they have a television set, so now you want a television set. It’s just this progression.

I was in one village and a man was cranking his karaoke machine until two o’clock in the morning – loud. He’s keeping everybody up. It’s a Saturday night. He’s partying. He’s in a hut that you can see through it.

So now people in the village will start building the concrete houses, to isolate people from the outside, from them – to isolate people from themselves, their own madness. That hasn’t fully happened yet in this village. I witnessed this event.

The person I was with said, ‘Oh my God. I can’t believe this is happening, that this person is doing that!’ I said, Wait. Wait for a few months. Because the roosters here still crow at 4am. They still have to wake up and go pick tea in the morning. But now this guy, selfish now. Wait until people are fist fighting out in the street. Wait. The real social problems haven’t even really started here, yet.

So, with the technology, mostly the electricity, comes this individualism. People want these supposed comforts, but these comforts are individualist in nature. And you start to lose track with what is happening with the community around you. And this is how it changes people’s relationships.

A man talked about how people come to church now and some don’t even sit next to each other anymore. Why? Because the technology has changed the relationships that they have with one another. It’s a barrier. Before they had to live in community with each other. Now they don’t.

One woman said ‘We used to go walk to the forest and work together. Now people take their motorbikes.’ Or, ‘Why did you go to the store and not tell me? I needed something. What’s going on? Are we still friends?’

Well, how does this make people feel about their neighbors? This is changing their relationships.

[I want to go back. How can people know that this is a bad thing, to let this modernization inside. They have a hot shower, they’re comfortable, it’s nice. They have the house that isn’t dusty anymore. So how are they supposed to know? And then you have the comparison of the village that this has happened before. So, do they just feel good about all this?]

I think it’s all just happening. They think it has to happened, so it happens. It’s the market system. They don’t have a choice. Because they’re not getting the education to self-sustain themselves. The only education they are receiving is to be pulled into a mainstream Thai society.

Or in other parts of the world, other types of mainstream society. But this is really about globalization. It’s a global market system. And this global market system is effecting their ability to survive. If they can no longer live off from the land around them, now they have to make money. Before they didn’t have to make money. Maybe they had a barter system. Maybe they traded. Maybe they just hunted and gathered.

[So, do they like it? Do they feel like this that natural life is a blessing. Or do they just don’t want it anymore. Or have no choice.]

The middle-aged parents are working in the “farm” to earn money and pay for the things they believe they now “need” – electronics, motorbikes and “education” – leaving their children to essentially fend for themselves in-terms of maintaining their responsibilities (particularly related to pursuing the preservation of their culture).

This may have been okay before when the culture was more self-contained socioeconomically. 11

However, nowadays the youth are essentially being left to the wolves of modern development because there currently are no village institutional social support systems in-place, like in mainstream society, to address such a sociological phenomenon.

This is one thing.

My experience is that what I saw is they are in shock, as I said. I don’t know if they necessarily feel good or bad about it, yet. One village is way out there with tar roads and new technology and say, ‘We are happier this way.’ But an older woman said it to me very clearly that ‘We know, the older people know that our culture is gone. But the younger people see it with a different lens. They don’t know any different.’ So to them, this is the new way. This is normal.

[Well, if you see this through the young people, then you see that modernization is good. ‘It’s good for us. I want to be modernized. I have all these amenities.’ So, how do you show people that’s it’s maybe not?]

Of the young guys said he is going to take care of his parents, this and that. And I said, ‘If you spend all your time in school and in the city, 30 years from now your parents aren’t going to be here in the village. You’re not going to have a home to come back to. Your not going to have this culture that you love to come back to. Because you’ve spent your time in the city, modernizing yourself.’

He just looked at me. It had this confused look on his face. It was clear that he had never thought about this. He just puffed up and said, ‘I just have to study! I have to study and graduate. This is the most important thing.’

They are in survival mode.

I said to another friend in the Karen village that, ‘While you guys sit there and watch television and play with your iPhone, and your young child is playing in the corner, doing whatever, at this point, your culture is in such a state that you don’t realize what is happening. That right now you are just watching a television program that is entertainment. But you don’t understand that that generation you are skipping, from imparting the cultural traditions that you learned…It’s okay for you to watch TV because your ethics and values are already instilled in you. But they are not instilled in your child. They will grow based on the way you treat them now. You cannot skip a generation.

This is what happened in America too, with the 60s revolution, in my limited perspective.

You have a generation that sort of skips a traditional way of life. You can’t remove culture. You can change culture.

One woman I talked to in the village said, ‘I have no stress. I know how to live off from the land. Oh. My tea was destroyed; now I can’t sell it. No problem. I’ll just go fishing today. I’ll get food and feed my family tonight. I’m not worried.’

However, her child does not know how to do that. You skip that generation that knows how to do this. And this is essentially what is happening – the way I am seeing it.

And this is what I have learned, through growth and a year and half of experience. And what I know is nothing. I know, nothing. It’s a nick of the surface. It’s just the concept. The concept of what is happening to these people is applicable to the world.