*The following is a cross-section view of the Indigenous Voices book and culture preservation project. The audio-visual version of this book — “Foreigner from the Future: A Moments’ Pause” — is currently in-production. Additional info (and a synopsis video can be viewed at http://www.jeffsjournalism.com/indigenous-voices*

INTRODUCTION: This project explores into the effects of economic development in terms of how it affects relationships amongst ourselves and with our natural environment.

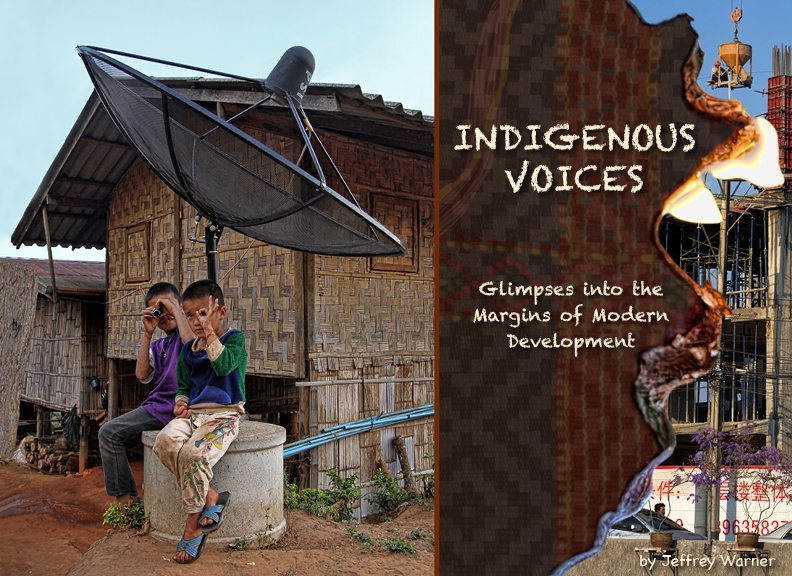

As a context for looking into this, we travel to northern Thailand. There, communities of indigenous peoples, who represent a nature intrinsic to us all, have for generations been living fairly traditional lives even in the wake of an encroaching modern world culture. However, their traditional cultures are literally vanishing as modernity is shifting centuries of learning and indigenous knowledge aside.

To better understand northern Thailand’s indigenous peoples and their overall situation, I’ve used the seamlessly paired integration of both text and lifestyle photography, prose, and in-depth interviews.

We, step-by-step, learn specifically about the effects that modern economic development has had on their communities. We explore what this may mean for all of us humans.

The first part of this journey provides general ‘exposure’ to village life as we at first attempt to detach from a modern world environment and relish real Thailand, which is nature. This is while we are acclimating to and learning from a distance about highland village life and how its being effected by outside influences.

After gaining greater insight, villagers 14-84 years old, from three different ethnicities, and from village communities at different stages of the global development continuum further open the doors of their homes. They help us understand more by using their ‘voices’ to express opinions and related experiences regarding how their communities have changed in more recent years. After being ‘exposed,’ the third section provides opportunity for us to go ‘back to the basics.’

Are you ready for this journey?

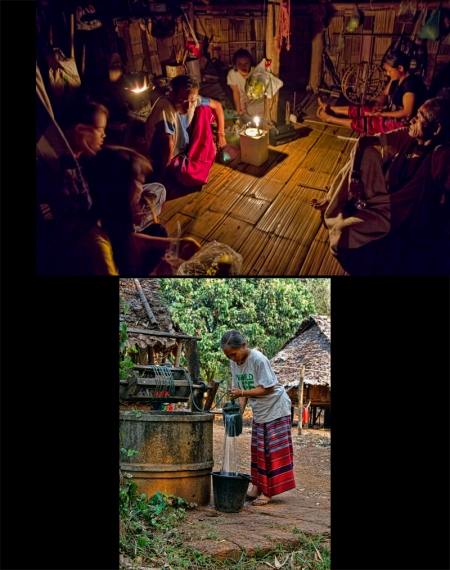

PART ONE

EXPOSURE: Naïve, my life was going to be forever touched by the highland villagers, as they pulled food and medicine from the forest and stood proud of their heritage. I would experience the nuances of village life with its wisps of wood smoke, early morning rooster crows and clucking chickens, and chilly nights as mountain air streamed through the walls of thatched bamboo huts. I would be warmed by open fires and the wholesomeness of family and community, pick tea and corn with them, and scour a mountain stream for fish to eat. We would laugh and take part in ceremonies together. I would also listen to their woes as holidays in the village are followed by a return to the city. I certainly didn’t understand at-first how their lives had been drastically affected by modern development. All I could do was observe from afar and pose questions, and each village experience exposed me to something new.

Within a short distance of Thailand’s rapidly developing capital city of the north, Chiang Mai, mountain dwelling ethnic groups, “highlanders,” live in a similar fashion to how our human ancestors once did. They’re more integrated with their natural environment than people living in the cities below them.

However, this is changing as the world market system and lifestyles associated with Western culture perforate the social fabric of the developing world and replace ethnically traditional lifestyles with those of a homogenizing modern world culture.

While the mindsets and related lifestyles of both the older and newer generations can be observed in northern Thailand, Chiang Mai, for example, with its slow paced and traditionally conservative culture, has evolved dramatically from what I had considered a “big city small town”into a city-like environment, especially with the development of shopping centers, worsening traffic congestion, and increasing environmental pollution.

This phenomenon follows suit with mainstream Thai culture as the younger generations are abandoning traditional agricultural life for the livelihoods associated with modernity – the I-Phones, designer jeans, new motor vehicles, and subsequent financial debt.

Farmers are selling their generations-old properties as investors purchase and fill in rice paddies with concrete. In this manner, a growing number of Western style businesses and condominium complexes grace Chiang Mai’s mountainous skyline, which is drastically altering the landscape of traditional communities and how people interact with one another.

Northern Thailand has ethnic groups, indigenous to the mountainous areas, that are in a sense being forced to become part of this modernizing trend. They, not unlike the Native Americans’ history and that of other indigenous peoples worldwide, now largely must depend on local and world market systems alien to them in order to survive.

Although many of these communities have for generations lived in northern Thailand’s mountains they are still not considered Thai nationals; therefore, many of them don’t have Thai citizenship necessary for receiving government social benefits. This situation is having a profound impact on their ways of life, making their future uncertain.

For the most part, villagers can no longer live in their traditional manner. Most now work on their own farms or at hard labor for the Royal Thai Forest Department.

Like other modern world communities they must now generate funds for life necessities, as well as the perceived material needs offered by Western style consumerism, such as processed foodstuffs and electronics. Many villagers with home communities located up in the mountains now live and work in the lowland cities, which creates a particular set of issues both outside and inside of the village.

In the village, alcohol and meth addictions are an ever-growing sociological by-product of this brave new world that co-exists with those villagers who are still attempting to live a quiet village life and are struggling to maintain the norms and values associated with their traditional culture.

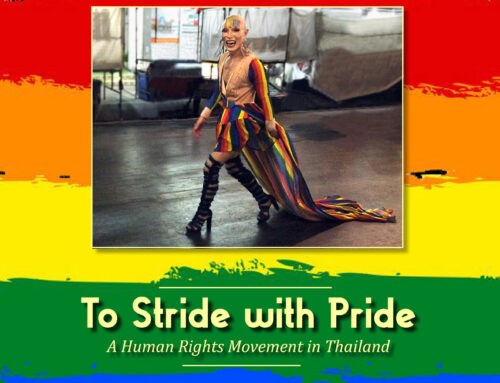

This is transpiring while village community members dressed in traditional clothing mix with younger generations wearing colored hair, T-shirts, and name brand shoes. They are mimicking mainstream Thai (and therefore, modern world) culture.

Overall, the villagers appear to be in shock, desperately trying to maintain their traditions while adapting to the encroachment of a modernized lifestyle that is pulling them in one television program at a time.

For many villagers it’s as though they’re simultaneously living fundamentally different ways of life — a mixture between their cultural heritage and that of the mainstream modern world.

In some villages, both open cooking fires and glowing television sets comprise standard furnishings in bamboo huts where families eat meals still containing food collected from the nearby forest. Sometimes a baby’s cries meld with the thumping of a karaoke machine, a result of electricity having been installed. Shiny new motorbikes are parked next to the satellite dishes pointing towards the sky, plugging villagers into what some of them call “the outside world.”

With the new roads, used largely for transporting cash crops, traffic jams are sometimes even an issue in some villages!

Many villagers, much like in what people may ignorantly consider more ‘civilized’ or ‘advanced’ cultures, want to keep up with their modernizing neighbors but don’t really know how to cope with their rapidly changing environment. The younger generations are looking to the outside world for examples of how to survive in a modern society. They have little to no clue which world existence paradigm they should identify with or to which one they belong.

For example, one can witness the stark contrast of a young Thai speaking villager clad in his or her traditional ethnic clothing while also wearing caked-on makeup or a hairstyle mirroring modern Korean hip-hop culture. The middle-aged villagers want to preserve their culture for which they feel responsible; however, these folks are also being enticed by modernity related conveniences. Most of the elders can’t identify with any of this. Most all of these villages are enduring what is a very real and tangible identity crisis.

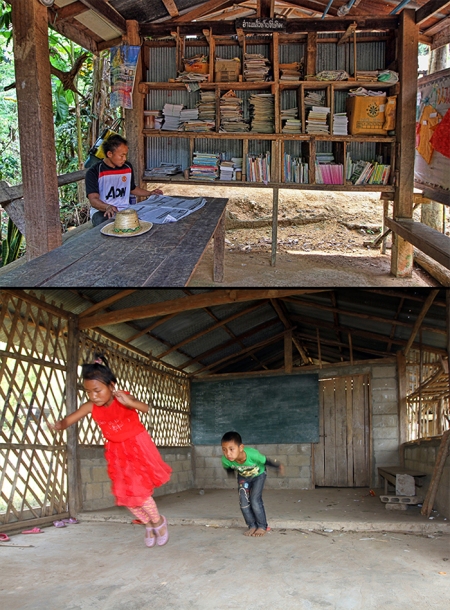

Paradoxically, this same modern infringement is bringing to the villagers the basic human rights necessities such as education, modern facilities, and improved health conditions.

Although it is likely impossible that what could be deemed ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’ can truly exist simultaneously, these more traditional communities can potentially serve as a contemporary social-scientific measurement of humankind in terms of how it is has been and is being affected at its core by modern development related phenomena. This includes how physical environment related changes alter relationships among ourselves and with our natural environment.

*****

This topic is a global issue. What’s transpiring among these ethnic communities has long since happened in First World, supposed more advanced, countries and continues worldwide. Likewise, Indigenous Voices isn’t only about these cultures; it’s about human beings as part of a global community.

Beyond providing a window into the seldom seen world of highland village life, this culture preservation project explores into the effects of economic development on the human species in terms of how it affects relationships among ourselves and with our natural environment. It’s about posing questions, formulating theories, and offering suggestions. We should perhaps take a moment to reflect: ‘What’s happening on Planet Earth regarding the supposed progress of the human species? Let’s take a closer look, at ourselves.’

On the one hand, there remains people living relatively primitive lives, who traditionally respect their elders and eat natural foods, and whose communities are in touch with nature. On the other, a First World, supposedly more advanced social order steeped in social and economic inequality, material acquisition, and environmental pollution among a host of other transgressions. Here we must prioritize; what do we humans really want? And what can we still learn, if anything, from supposedly “less civilized” cultures?

Highland Voices is also a memoir. It’s my analogous journey in a quest to reconnect with my root system, back to a point of natural innocence literally on the opposite side of the planet from my birth. This stems from a driving force to access what I consider to be the heart of humanity, i.e. the nature intrinsic to us all, and which perhaps manifests more in the hearts and lives of these highland people living in their natural environment…

With many semi-informed questions now in my heart and mind, I wanted to learn more about villagers’ ways of life, to hear their voices, details, the bad and good, about how economic development was affecting them and their cultures. How were they adapting?

Villagers from three ethnicities – Karen, Lahu, and Hmong, ranging in age from 14 to 84 years, and from communities each undergoing a particular stage in the development continuum – open the doors of their homes and helped me further understand.

THE FOLLOWING ARE THREE OF THE NINE PRIMARY ‘VOICES’ INVOLVED WITH THIS PROJECT

Jasuu Jamoo, 66

“When I moved here nearly 40 years ago, only a narrow pathway carving through the jungle allowed us contact with the outside world. There was no electricity.

Walking to the city about once a month took many hours…”

“I didn’t have outside influences. The road is good now, and the city life is coming in to the village.

Villagers are copying behavior from the outside, especially the teenagers…”

“To be Lahu is to collect your own food and respect the elders by giving them the first fruit. We used to do both. Everything has changed. It’s not good.

We want to preserve the culture. We are contributing to the changing of the culture.

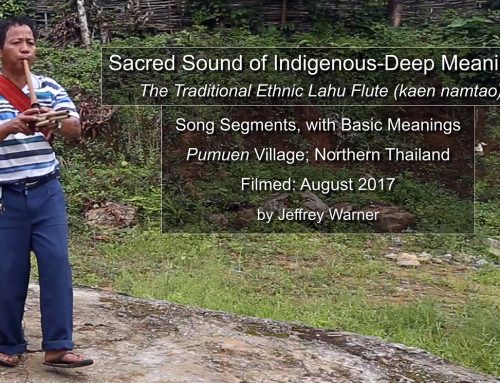

I wish the real sense of community through the cultural traditions would return. This would make the spirit of everyone come back into harmony…”

“I know that we need to preserve the culture. However, I don’t know exactly how to do it. All I can do is manage my time while teaching.

The first thing I teach the children is how to play the flute…”

“While I am still alive, I will reinstall and preserve the culture. If nobody preserves the culture, everything will be gone someday.

If nobody helps, it will be gone.

If we don’t teach well enough, technology might become villagers’ God…”

“I remember the community relationship building activities, especially during the New Year’s celebration

when we would play courting games and dance together…”

“Sometimes 30 people would be playing a song together. Now there are very few regular activities in the village for preserving the culture.

People dance and wear the traditional clothing on the outside because of what they believe on the inside.

They treat each other with respect because of what they believe.

Now many villagers wear non-Lahu costumes…”

“A problem is that villagers are marrying people from outside the village and staying in the city to work and live.

When villagers move to the city, they lose touch with the feeling of being Lahu and don’t believe anymore, enough to do the cultural activities from their heart.

Now it seems like some people want to dance and some don’t…because they have a motorcycle, a TV. They have many things and do whatever they want…”

“I know that modernization is having an influence. My daughter also has electricity in her home, a cellular phone, motorbike and a color television…”

“Before there was television here, we would visit and talk together. Now these relationships have been erased.

You can get an education in the city. However, when you stay here in the village, it should be a Lahu life. Don’t bring city life up to the village.”

***

“The New Hmong: Becoming Clean”

Pai, 57; Fon, 21

“Now we have modernization. Everyone else is changing. How can we live without change? We have to change.

There are people in the village maintaining the original Hmong way of life; it is difficult for them…”

“We have to keep developing the modern way. We have to adapt to be like the others.

We love to stay here in the village. We don’t think city people have a better life. We don’t really want to be like them.

We do want others from the outside to see that we are developed…”

“In the past, people from the outside would see that our Hmong way of life is undeveloped and dirty.

We have to show that we are developing ourselves, becoming clean…”

“In the past, we looked like tribes people. We used wood for cooking; now we use gas.

We use high technology, such as a rice cooker and a machine for washing and sewing clothes…”

“Living in a bamboo house was cold and dusty. It’s about comfort. We have to keep developing and have a better life.

Because of modernization and technology, our way of life has totally changed…”

“Thirty years ago, only grass and trees surrounded our bamboo huts. There was no electricity and no paved roads, resorts or restaurants.

This all especially changed about 10 years ago. Now the trees have been cut, more houses built mostly within the past two years.

We used to grow upland rice for consumption. Now we have to buy it in the market…”

“Now we grow cabbage and corn for income. Now we often eat corn instead of rice.

The village shaman died eight years ago; now we see the doctor in the city.

The New Years and wedding ceremonies are still the same though.

However, we now have to buy the alcoholic beverage used for the traditions. We used to make it…”

“In the past, there was more safety in the village. We didn’t lock the doors of our homes. Now we have a refrigerator, DVD player and a TV.

We need to lock the doors because we don’t know who will steal our things. Safety first! …”

“As far as seeing many tourists here, having a tar road and traffic in the village, many of us love that people come to this village. The more people, the more fun.

“We like the present time. In the past, there wasn’t a good road. We had to walk to the farm.

Now we can use the car for work and easily travel to another village.

We can have development and cultural preservation at the same time…”

“We maintain our traditional culture. The Hmong dress shows that we are Hmong. We still do things like make rice cakes.

“We maintain our traditional culture. The Hmong dress shows that we are Hmong. We still do things like make rice cakes.

We still make handicrafts and embroider to show that this is a Hmong village.

We go to school and learn to speak Thai, but we speak Hmong with each other at home.

If and when the older generations die, the new generations can continue the culture.

Even if Hmong people live in the city, even if they don’t know the Hmong language, they can still preserve the culture.

The Hmong’s way of thinking has totally changed. The picture that we can remember of the past, it’s not like this, this way of life.

The older generations have a different picture than the newer generations of what is really Hmong…”

“In the past, a concrete house would not be Hmong. But now because of modernization, it is Hmong.

Now we need to make money to build the concrete houses to replace the bamboo houses, to show that we are clean.

We want to develop ourselves.

If we think like a traditional Hmong, everything about our way of life has totally changed.

However, for a modernized Hmong, our current way of life is just normal.

If in our minds we can see that nothing has changed, we can enjoy our life.

If someone were to come here with a magic wand and bring us back 30 years to the original Hmong way of life, we wouldn’t want that.

We don’t like the past. We love this kind of environment. We don’t have to live a hard life anymore. Our life is more comfortable.

This is the new Hmong…”

***

PART THREE

EXPOSED: BACK TO THE BASICS

Tior, 48

I’ve lived in this 10-village settlement area, Phabat Huay Tom (“Buddha footprint”), for 36 years;

in this village, Nam Bor Noi (“village with the little well”) for 16 years…”

“Living like this is fine. It’s a quiet and peaceful life…”

“Eighty percent of the (Karen) villagers living here in Nam Bor Noi don’t need electricity or running water…”

“If someone here has money and needs these, or if they don’t follow the rules, they can buy land elsewhere, build a house and do whatever they want…”

“The villagers and the Thai government support preserving this traditional way of life. We want to keep it special. We are preserving our way of life…”

“In the future, I don’t know what will happen. The other nine villages are modernizing. However, I am satisfied to stay like this…”

“This is sacred land. It belongs to Kru Ba Wong, the great former monk who founded this area and who we worship from our core.

He taught us to follow Buddhist principles, be good people, eat vegetarian, not modernize and maintain the culture. I want to preserve this…”

“Other people feel like they need material things to be satisfied in life…”

“I think the most important thing for a happy life is to have my own space and food; I can survive. Having a car is a small thing compared to this…”

“The Thai government surveyed this village, asking us if we want solar cell technology. Most of us believe that electricity is dangerous for this type of house.

We asked who will pay for the electricity, water and infrastructural repairs. For me, I would however like to have more light when I’m eating. I am okay…”

“A major challenge I face nowadays is finding roofing materials for my house. The climate has changed and the grass is now hard to find.

The leaves used as an alternative last only a couple of years…”

“I worry most about land ownership. I don’t have any rights to this land; it’s owned by the government.

If I don’t have land for growing rice, for eating, this is a big problem.

Some people, including myself, rely on doing hard labor (farming) for making a living…”

“Sometimes there is no work. I worry about this too, and getting sick, but not too much…”

“If I had to move: The reality is that I am here. If I’m not here, it means I’m dead.

When we were born, we didn’t have anything; life was fine. But if we are greedy and selfish, it ruins our life and our relationships…”

“Our culture is becoming like this. Everyone should be a good person. I don’t know if I’m a good person.

I’d like to know how to be one. I know that I’m not greedy or selfish…”

“I want to transfer to my children what it feels like to live this traditional way…”

“I don’t expect that the newer generations will preserve this culture. However, once you’ve been in this environment, it will be with you forever.

Because the younger generations have lived like this, it will be with them forever…”

“This village is very special. It’s not just foreigners who want to observe our way of life. Other Karen villages need to see this as well.

This way of life is healthy. It’s something that money cannot buy.”

EPILOGUE

While village life certainly involves challenges and hardships, perhaps overlooked by those who may tend to romanticize this way of life, this livelihood in many ways appears fundamentally far more natural, and perhaps healthier, than the lifestyles generally associated with those of the modernized world.

With warm welcoming smiles, curious gazes, and near selfless generosity, these mountain dwelling people revealed something that has perhaps been dampened by the supposed progress of modern development – namely, a connection with our natural roots and with each other.

People I’ve talked with appear to accept modern globalization as a phenomenon that will take place regardless of whether we as a global community want it or not. Perhaps, this is an untruth.

Humankind can determine its destiny. We can choose how we live, within the boundaries of our available resources. Let’s choose wisely…

*ADDITIONAL INFO ON THIS BOOK IS AVAILABLE AT: http://www.jeffsjournalism.com/indigenous-voices/

Leave A Comment